As a country located in South America according to top-mba-universities, Chile was inhabited by indigenous communities, more or less autonomous, almost all belonging to the Araucani family, who came into contact with the Iberian conquistadors in 1535, when the small army of Diego de Almagro, to whom Francisco Pizarro had entrusted the task in Lima to extend the Spanish colonial empire to the south, after crossing the southern bank of the Maule river, it entered the Araucanian territory. After two years, Almagro was forced to retire; Pedro de Valdivia, who replaced him, founded the city of Santiago in 1541 and Concepción in 1550. Meanwhile, the Araucans had found in Lautaro a brave and brilliant leader who led them to counterattack and managed to stop the enemy advance. In 1553 the two armies faced each other: defeated, Valdivia was captured and killed. The Spanish conquest, however, now irreversible, slowly but progressively consolidated and the Araucanians had to take refuge in the far south. The history of Chile, administered as Capitanía General in the context of the viceroyalty of Peru, it was substantially confused until the middle of the century.

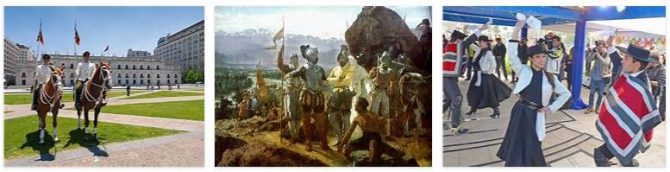

XVIII with that of all Hispanic America. Protagonist of the struggles for South American independence, it was the scene of a first, important revolt in 1781, but only after the Napoleonic event was there a substantial change in the situation. The patriots had their center in Concepción, where Bernardo O’Higgins worked, a liberal who on 18 September 1810 reunited a Cabildo abierto with other patriotsin Santiago. The Spanish governor García Carrasco was sacked and a revolutionary council was installed, headed by Mateo de Toro y Zambrano. The disagreement between O’Higgins, determined to arrive at the proclamation of independence, and other leaders of the movement in favor of maintaining a link with Spain, ended up favoring colonial interests and O’Higgins, defeated by the Spaniards in 1814, fled to Mendoza and then to Buenos Aires. In 1817, after having found an understanding with General José de San Martín, crossed the Andean mountain range with the latter and on February 12, 1818, in Santiago, both proclaimed the independence of Chile. On April 5, with the victory of Maipú, they overcame the enemy resistance and guaranteed freedom to the country. The reformist spirit that inspired O’Higgins in setting up the structure of the state disturbed the Creole aristocracy and the ecclesiastical hierarchy and in 1823 he had to give up power and move to Peru. The departure of O’Higgins marked for Chile the beginning of a period in which the leadership of the Republic alternated now this now that caudillo, which always dictated new Constitutions (for example, in 1823, in 1826, in 1829); in those same years the conservative and liberal parties were formed. In 1829 the reconfirmation of the liberal Pinto as president and the immediate reaction of the conservative general J. Prieto started a civil war. Victorious at Lircay the following year, the Conservatives took power and remained there for thirty years. The architect of the economic progress made in those years was the minister D. Portales who, if he endowed the Republic with a Constitution (1833) which ensured the oligarchy the levers of command, encouraged trade and production and developed the port of Valparaíso. The fruits of Portales’ policy matured in the war fought, alongside Argentina, against the Peruvian-Bolivian Confederation (1836-39); the triumph obtained in Yungay (January 20, 1839), which led to the final victory, helped to strengthen the prestige of Chile. M. Bulnes’ presidential terms (1841-46 and 1846-51) and M. Montt (1851-56 and 1856-61) increased the strength of the country, both economically and militarily; the boost given to culture is also noteworthy, with the opening of the University of Santiago to the best thinkers from all over Latin America. With JJ Pérez (1861-66 and 1866-71), Montt’s successor, the dominance of the conservatives ended.

The rise of the liberals, who took over with F. Errázuriz Zañartu (1871-76), then with A. Pinto (1876-81) and D. Santa María (1881-86), represented the consequence of the socio-economic transformations that have occurred in the country since the time of Portales, also as a result of massive German and British immigration. Entrepreneurial and mercantile classes pressed for the overcoming of the old agricultural structure; a national bourgeoisie was sprouting. The so-called “war of the Pacific” (1879-83), which saw the Chileans oppose the Peruvian-Bolivian alliance, ended with a great victory for Chile. Santiago’s aims, centered on the control of nitrate production, were satisfied with the purchase of Tacna and Arica (Tacna, in 1929, would be returned to Peru) and the conquest of the coastal strip of Atacama with the port of Antofagasta. The happy outcome of the “war in the Pacific” further stimulated the economic development of the country, consequently increasing the social ferment.