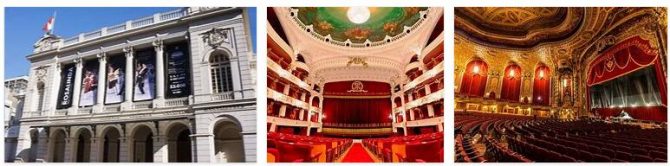

CULTURE: THEATER

The ballet arrived in Chile, like the opera, only in the nineteenth century, with performances by foreign companies and ensembles. A national production, albeit of little importance, and dance schools have sprung up in the present century; after 1940 the first companies were formed (Ballet de la Universidad de Chile and Ballet Clásico). Rich is the heritage of folk dances, a pre-eminent part of Chilean folklore. Among the best known popular dances and in vogue until the century. XIX we mention the threshing dance (huachambe), the dance in pairs agua nieve, the zapatera. The ancient magical dance of the Araucani in honor of Canquem should also be remembered, the sacred bird of the rain, still performed today on the occasion of Catholic religious holidays, and the numerous Creole dances, with evident Western influences (the Argentine cielito, pericón, resbalosa, cuando; the Peruvian zamacueca or cueca, considered a national dance).

At the beginning of the sixties, with the activity of the Ictus group, the avant-garde theater entered the scene. Among the major exponents of the group, J. Diaz (b. 1930), influenced by the experimentalism of the European “theater of the absurd”. The student movements of 1968 led to greater politicization of repertoires in a short season immediately crushed by Pinochet’s military rule (1973). Many artists emigrated and those who remained were limited to presenting escapist shows. Things began to change in 1984, thanks to a policy of cautious liberalization of the regime, as a result of which new groups were born and new talents emerged, with repertoires attentive to the problems of the country and its citizens. Social denunciation and news were at the center of Chilean theater in the seventies and eighties.

CULTURE: CINEMA

With primitive technique, about eighty films were produced in Santiago, Valparaíso and elsewhere in the silent period (from 1917 to 1929), a couple of which were awarded among the best in South America. The advent of sound caused a crisis that lasted almost a decade. In the 1940s and 1950s the studios were modernized, the contribution of foreign capital and filmmakers was sought, and a cosmopolitan production was aimed at; on the other hand, in 1958, for the neorealistic aspects, was noted La caleta olvidada (The forgotten bay) by B. Gebel. A new cinema was born in the 1960s in the wake of the documentary A Valparaíso (1962) by J. Ivens and following the example of cinéma-vérité (Morir un poco, 1966, by A. Covacevich), stimulated by university circles and by the Latin American festival of Viña del Mar (1966) and finally favored by the rise to power of S. Allende. The so-called “cinema of Allende”, which was not all politically allendist, but was the first and only national cinema in the history of the country, lasted less than three years, that is to say as long as the government of Unidad Popular. In that period, moral and civil fervor was ensured, along the lines already presented in the Manifesto of Chilean filmmakers (1970) for an “authentically national and, consequently, revolutionary culture”, by the conviction that “revolutionary cinema is not born by decree”. There Valparaíso, mi amor by A. Francia, Tres tristes tigres by Raúl Ruíz, Caliche sangriento (Blood Saltpeter) by H. Soto, El chacal de Nahueltoro by M. Littín. The creative impetus was also favored by the birth of a Film Institute and a section of experimental cinema. Among the documentaries, Casa o mierda (1970) and Qué hacer? (What to do ?, 1972) due to collectives; Compañero president (1971) by Littín, El primer año (1972) by P. Guzmán. Among the narrative films La tierra prometida (1972) by Littín, It is not enough to pray (1972) by France, El realismo socialista (1972) by Ruíz, voto más fusil (Vote plus rifle, 1971) and Metamorfosis del jefe de la policía politics (1973) by Soto, which was the last. Starting in 1973, all the filmmakers (those not imprisoned or killed) left the country; under the Pinochet regime there was no longer a Chilean cinema, while there was a significant production of directors in exile. After Diálogos de exiliados (1974), Ruíz shoots in France La vocazione Sospesa (1978), first prize (ex aequo) at the Sanremo Art Film Festival; Littín makes Actas de Marusia (1975), The appeal of the method (1978), presented at the Cannes Film Festival, and Alsino y el condor (1982); Guzmán, after the documentary La batalla de Chile: lucha de un pueblo sin armas (1973-75), made his debut in Cuba with the narrative film La rosa de los vientos (1983). Excellent first work Ardiente paciencia (1983) by Antonio Skarmeta, exiled in Germany. In the nineties it was Ruiz who represented Chilean cinema on international circuits with Tre vie e una sola morte (1996) and Il tempo regato (1999). The filmmaker again directs Klimt (2006) and La recta provincia (2007), but in the years at the turn of the millennium new authors and new productions testify to the vitality of Chilean cinema. Marcelo Ferrari, Silvio Caiozzi and Carmen Castillo are just some of the names hosted in major international festivals. As a country located in South America according to collegesanduniversitiesinusa, Chile is also an active participant in the production of I diari della motocicli (2004), a film directed by the Brazilian Walter Salles and focused on the journey that helped transform E. Guevara into “Che”. A mention also deserves Andrés Wood (b. 1965), who became known internationally with the award-winning Machuca (2004), the story of a friendship that crosses social classes in Allende’s Chile and, later, Pinochet.