The beginning of the Gothic style in England dates back to 1174, the year in which a French master, William of Sens, began the reconstruction of the Canterbury choir (destroyed by fire) in Gothic forms derived from Île-de-France. But apart from this and a few other isolated examples of French derivation, England immediately developed a national Gothic style that tended to be antithetical to the continental one due to its indifference to any structural coherence and to technical-constructive problems. Characteristics of the English Gothic are the “add-on” plants (double transepts, square transepts and choirs, the chapels of the Virgin behind the choir), the western facades with no relation to the structure of the interiors (often simple screens as in Wells and in Lincoln), western and central towers and spiers, massive walls burdened with rich carved ornamentation, ribbed vaults, intertwined to form complex star and fan designs, but lacking structural functions: aspects that anticipate the late Gothic styles of the continent. The greatest examples of this early phase of English Gothic (Early Gothic) are found in the western region (Glastonbury, ca. 1186; transepts and nave of Wells, ca. 1191) and in the north (Ripon, ca. 1175; Hexham; Whitby; choir of Rielvaux; York transepts). The choir of Worcester (1224), Lincoln Cathedral (1192), with vaults decorated with palm ribs, Salisbury Cathedral (1220-60) built entirely in this style, the choir and transepts of Beverley (1232) are exemplary manifestations of the primitive phase of English Gothic. In the field of military architecture, the Norman keep was replaced by the regular-plan castle with concentric curtains interspersed with towers (Conway, Caernarvon, Harlech, Beaumaris, erected by Edward I in Wales in the last quarter of the century. XIII). Also characteristic are the English chapter rooms, with a circular or octagonal plan (Lincoln, ca. 1250; Southwell; Salisbury, ca. 1275; Wells, ca. 1300). Between the mid-thirteenth and mid-fourteenth centuries, English Gothic is characterized by decorative exuberance (proliferation of decorative vegetal motifs, star vaults, with complex openwork and, from about 1300, asymmetrical) and by the renunciation of spatial definition (environments hall, decks, ribs without sails, three-dimensional ogives, etc.).

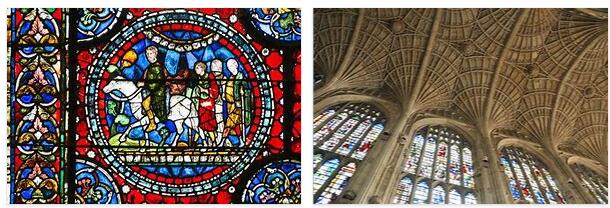

According to globalsciencellc, the greatest examples of the Mature Gothic style (Decorated Style) are the Choir of the Angels of Lincoln (1250-80), the eastern part of Wells (1285-1332), the choir of Bristol Cathedral (1298), the Octagon (1322-42) and the chapel of the Virgin in Ely, the cathedral of Exeter (facade begun in 1346). At the same time an alternative to the ornate style developed in the perpendicular Gothic style which, born as a court style, became the typical expression of the English late Gothic after the mid-fourteenth century. The perpendicular style replaced the plastic decoration with a geometric decoration with vertical and horizontal linear elements that more precisely defined the spans and framed rectangular fretwork panels. The masonry lost all importance, existing only as a support for linear and openwork decoration, or was even abolished by the proliferation of large openwork windows with polychrome and figured glass which, although already widespread in the century. XIII, reached in this period the maximum decorative importance (Coronation of the Virgin, Gloucester, cathedral), perfectly fitting into the architectural ensemble. The vaults are star-shaped or fan-shaped, with increasingly complex interweaving of ribs (Gloucester, choir, 1337; cloisters, 1357). Extremely rare are the surviving examples of English Romanesque and Gothic sculpture, almost totally destroyed in the Reformation period, and essentially limited to the sculpted architectural decoration (caryatids of the chapter house of Durham Cathedral, ca. 1130; column-statues of St. Mary in York, 1180; statues within niches of the facade of Wells Cathedral, 1216), to the decoration of architectural elements (capitals, cornices, portals), and to the type of tombstone with effigy of the deceased (Statue of King John, ca. 1230, Worcester Cathedral).

The architectural decoration is sensitive to multiple and in some cases contemporary influences (Italians, Byzantines, Germans, Aquitanians, Poitou, Île-de-France) which presuppose the importation of workers. Tomb sculpture and portraits passed from typically insular realism to courtly and refined forms of continental import and cosmopolitan style (late Gothic period: Queen Eleanor and Henry III, bronze, Westminster Cathedral). The rare examples of polychrome alabaster statues (Madonna Flatman, sec. XIV; London, Victoria and Albert Museum), type of production, traditional and exported, very flourishing in the late Gothic period. The fragmentary Romanesque frescoes of Canterbury Cathedral and the Abbey of St. Albans, the Gothic ones of Winchester (chapel of the Holy Sepulcher, ca. 1230) and Westminster are among the very rare examples of painting that survived the reformist inconoclasm. The Wilton Diptych is linked to the international Gothic style (late 14th century). The monastic schools of miniature (St. Albans; Westminster), already flourishing in the pre-Romanesque period (6th-10th century), reached their maximum splendor in the 18th century. XI and XII for the originality of the decoration and the abundance of figurative scenes often linked to Carolingian prototypes; bibles, psalters, bestiaries constitute an iconographic heritage from which figurative arts and crafts (embroidery, ivory, stained glass) drew; in the sec. The naturalistic decoration prevailed in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the realistic character of the figurative scenes was accentuated and continental influences began to be felt, especially French and German. In the sec. XV and XVI the perpendicular style was applied in large buildings such as churches, cathedrals (Sherborne, 1430) but above all in chapels (Westminster, chapel of Henry VII, 1503-19; Cambridge, King’s College Chapel, 1446-1515; Windsor Castle, St. George’s Chapel, 1481) and in spacious parish churches with flat wooden ceilings, stained glass walls, high pillars: all elements that translate a trend towards spatial unification (Bristol, St. Mary Redcliffe, Norwich, York, Coventry etc.). From the layout of the monasteries partially derived that of the university colleges (Oxford, New College, 1386). In the first decades of the sixteenth century the commissioning of the Church almost completely ceased (no more religious buildings were built practically until the fire in London in 1666) and of the court; instead civil and private building flourished, which expressed itself in the country houses of the Tudor aristocracy.